When the Machine Becomes Too Complex, We Start Describing It as Alive

Part I: the collapse of categories and rethinking metaphors of biology, code, and control

Biology is not the inspiration for technology. It is the original technology.

It is ancient, stochastic, redundantly fault-tolerant. Cells already compute, proteins already encode, networks already adapt and reinforce. This is technology that stores, senses, adapts, and even forgets.

And yet, we still speak as if biology and computation are distinct paradigms. Perhaps it’s the overwhelming chasm (and huge opportunity space) that exists between powerful ancient biological tech and our ability to reliably harness and integrate the massive potential that’s been steadily evolving over billions of years. Some even argue that our capacity to turn silicon into some version of life will outpace our ability to transform life into a programmable platform for human flourishing. Maybe the cure to all disease is to one day upload your consciousness into a form that exists outside of the vulnerabilities of physical life.

But much of this thinking lives on a foundation of technological classification that today feels outdated, shallow, reductionist. We’ve been taught to think in categories: biological versus artificial, evolved versus engineered, wet versus dry. Employing language to give shape to the unknown.

The more abstract and obfuscated our silicon systems become, the more biological our language for them becomes. And the more programmable and interpretable biology becomes, the more computationally we describe it.

We are living through a mirrorfold moment where the metaphor reverses direction. We’ve always just been trying to make machines a sort of biology that we can optimize and control. We increasingly use biology to explain what machines have and are becoming. And in the process, we’ve collapsed biology into the language of code, because code seems to be the only metaphor we trust with power.

The First Inversion: Making Machines Familiar

Even at the earlier stages, when machines were more linear and legible, we borrowed biological metaphors to help build and explain them.

These were aspirational functional analogies that not only gave direction, but were chosen to make the strange feel approachable, familiar. The machine was a new alien logic, biology helped domesticate it.

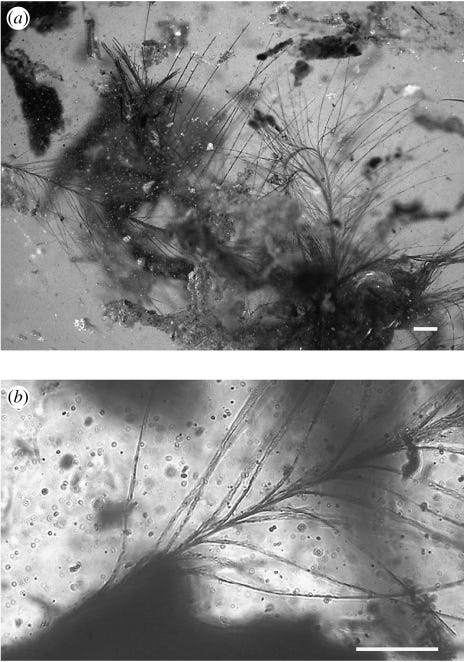

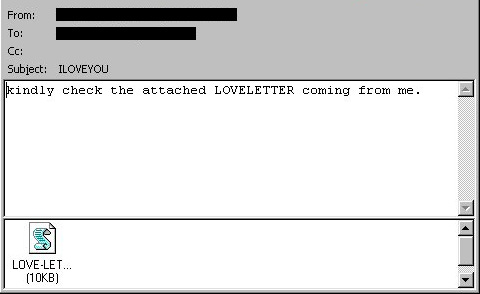

We did things like naming malicious code “viruses” because the biological infection metaphor helped us understand propagation, defence, and immunity. In fact, it could be said that one of the most powerful and destructive computer viruses in history was “love”.

The language worked because the machines were simple enough that we could see through the metaphor to the mechanism underneath. When we said a computer had memory, everyone understood this was different from human memory. The metaphor stayed transparent. We could see the gears turning beneath the biological framing.

This was borrowing without consequence. The metaphors served us, made complex operations feel graspable and gave us handles on abstract function.

We were still the authors. The metaphors stayed under our control.

The Second Inversion: Shrinking Biology to Fit

As our understanding of biology deepened and our ability to engage, edit, and manipulate living systems advanced, we began collapsing biology into the logic of machines.

DNA is code. Cells are factories. CRISPR is a text editor. Metabolism is a circuit.

The metaphor inverted. Computation became the source, biology the target. And this one carries weight. When we call DNA “code,” we’re not making an analogy, we’re making a claim about what biology fundamentally is.

Philosopher Thomas Nagel critiqued the reductionist approach back in 1974 in his essay What Is It Like to Be a Bat. In his piece, Nagel challenged the scientific and philosophical tendency to reduce complex, irreducible phenomena, like consciousness, into frameworks that feel familiar and manageable. He writes, “philosophers share the general human weakness for explanations of what is incomprehensible in terms suited for what is familiar and well understood, though entirely different.” He warns that this strategy works only by critical omission: “Without consciousness, the mind–body problem would be much less interesting. With consciousness it seems hopeless.” This kind of reduction succeeds by subtracting the very thing that makes the thing what it is. This is done even when what matters most is precisely the part that escapes that frame.

When we call DNA “code,” we’re attempting the same reductionist move, but biology, like consciousness, resists this incomplete translation into terminology that fails to capture it. These metaphors largely feel powerful because they quietly exclude the powerful and challenging reality that makes biology, biology.

Biology is not symbolic instruction. It’s not executed line by line, nor fully knowable through formal logic.

Biology mutates mid-runtime. It forks, fails, adapts, exapts. It evolves through noise, not design. The instructions don’t just execute, they rewrite themselves. They get copied wrong, and sometimes those errors become features not bugs. When engineered systems hit a fatal error, execution stops. When living systems hit one, ecosystems shift.

The asteroid that collapsed the dinosaur world didn’t reboot the past, but it did open up ecological space for mammals to radiate into bats, whales, and primates. This emergence was only possible when the old architecture failed. These were not predesigned lineages, but through catastrophe, biology inherits possibility.

This collapse of complexity into narrow metaphors can be harmful. It flattens the weirdness of biology into the neatness of something that it is not. It strips away the redundancy, the beautiful inefficiency of systems that work not because they’re optimized but because they’re resilient. Your machines are getting more complex, becoming weird, but biology has always been wonderfully weird and that is it’s strength.

Of course, there’s another reason we keep trying to collapse biology into simpler terms like code. Code can be owned. Code can be scaled. Code can be controlled.

Metaphors shape markets and the machine metaphor is profitable. It’s easier to file IP on programmable organisms than ambient intelligences. The computational metaphor is both conceptually limiting, and economically strategic. It transforms biology into something that fits existing frameworks of ownership, production and value extraction.

So we reach for metaphors that convert biology into a product, not because they’re true, but because they’re strategically available to the systems that allocate power.

But maybe it’s time to rewild our metaphors. To remember that not all intelligence needs to be encoded to be real. Legibility does not equal liberation.

The Present Paradox

And so we arrive at a strange paradox.

We use machine metaphors to condense and domesticate biological complexity, creating an illusion of control. But as our machines grow less controllable, as AI resists full comprehension, we reverse course and explain this artificial intelligence through the very biological frameworks we keep trying to transcend.

We prompt strange intelligent machines that hallucinate, but biological circuits are being engineered?

The metaphors don’t trace understanding, but the illusion of understanding. We keep reaching for whatever framework feels most mastered, even when that mastery proves to only exist inside the metaphor itself.

Let’s accept for a moment that the delineation between biological tech and silicon tech is largely arbitrary and superficial. That these seemingly separate technological paradigms are in fact evolving together, borrowing metaphors from one another, improvising, misusing, repurposing. The line between the two can begin to blur.

A deeper pattern hidden in this metaphorical collapse is free to emerge. The same logic that drives our reversing metaphors and the way we oscillate between explaining biology through machines and machines through biology can go on to reveal something more concrete about how innovation actually happens.

What Comes Next

This leads us into the realm of technological exaptation.

In evolutionary biology, exaptation refers to: “features that now enhance fitness but were not built by natural selection for their current role”. An example of this is bird feathers, which first seem to have emerged in dinosaurs that that weren’t able to fly. But once feathers existed, evolution, that works with what’s available, adapted them for flight. Wings weren’t rationally designed, they were evolutionarily repurposed.

From this perspective, I believe the relationship between biology and computation can look like one long story of exaptation. As much as biology inspires and informs computational aspirations, computational tools designed for completely different purposes are also seen resurfacing in biology, finding second lives and new meaning.

In Part II, I’ll trace a chain of exaptation to show how silicon tech and biological tech are both systems caught in the same evolutionary logic. How they borrow from each other not through inspiration, but through direct architectural inheritance.

From the brain’s visual cortex to convolutional neural nets that lead into biomedical imaging architectures like U-Net all the way to their migration into AI art engines like Stable Diffusion. I will go into a beautiful journey of exaptation from classifying objects to segmenting cells, and analyzing medical images to generating art.

This goes beyond interdisciplinary exchange. This is evidence of something deeper. These are co-evolving forces in a shared nature that may be different than the one we imagine holds them distinct and separate.

The evolving repurposing of tool and technologies across domains is a recurring pattern, a predictable feature of co-evolution, a strategy that can and should be tapped for innovation. Exaptation is not aberration, it’s the engine of transformation. The afterthought becomes the breakthrough.

Biological evolution masters this art, tinkering without foresight yet arriving at innovations appearing elegantly intentional in retrospect. Technological evolution follows parallel paths, academic curiosities become profound tools when context shifts, and serendipity becomes strategy

We are likely sitting on a treasure trove of powerful technologies that already exist, scattered across industries that have no idea they’re developing each other’s futures.

Beautiful essay as always. Cheers!

Brilliant breakdown of metaphor collapse. The observation that we reached for "code" not just for conceptual clarity but because it fits IP frameworks is sharp. When Nagel talked about reduction erasing what matters most, he was basically calling out how explainability bias can erase complexity. Biology doesn't execute linearly, it drifts through noise and sometimes fail states become fetures. Part II sounds super interesting, excited to see the U-Net journey.