From Microscopy to Midjourney: Is Biology Responsible for AI Art (slop?)

Part II: Tracing technological exaptation across collapsing categories and why it matters for innovation

What if biological technology and silicon technology were never truly separate paradigms? What if we’ve been describing a single evolutionary process using two incompatible vocabularies, switching between them based on which framework temporarily offers better purchase on what we’re trying to understand or control?

Part I explored how metaphors collapse in both directions: biology described as code when we want to feel in control of its complexity, machines described as alive when they become too complex for what we imagine a machine to be. The oscillation goes beyond linguistic convenience and suggests that the categories themselves might be arbitrary.

In this piece I want to move from metaphor to mechanism and trace a specific lineage of field agnostic technological evolution. This is a story that begins with electrodes in cat brains, somewhere in between goes from recognizing cats to detecting cancers, taking street mapping architecture and applying it to cell segmentation, then magically ends with machines generating images from text prompts.

It’s a beautiful progression where we see architectures escape their purpose, migrating across domains, and finding impactful second lives in unexpected places.

This can be seen as a form of exaptation. Feathers becoming wings. Medical image segmenting architectures becoming generative dreamscape engines. The same logic operating across what we are led to believe are different substrates.

Ultimately pointing to something strategically important. We’re likely surrounded by powerful technologies that already exist, scattered across fields that don’t yet recognize they’re developing each other’s futures. The challenge isn’t always invention. Sometimes it’s recognition.

From Neurons to Neural Networks

Let’s start at the brain’s visual cortex, the approximately 2mm thick, intricately folded tissue at the back of your skull that has been solving image recognition for a long time. Animal visual systems have been extracting structure from light since the early Cambrian, and yet it seems only recently that we began advancing the incredibly crucial survival trait of seeing and being seen from flesh to silicon.

The actual physics underlying image formation was observable long before we understood the biological architecture. Around 400 BCE, Chinese philosopher Mozi watched light pass through a small aperture in a darkened room and observed the world invert itself on the opposite wall. The camera obscura effect. Reality flipping through a pinhole. A thousand years later, Arab mathematician Ibn al-Haytham would take these observations and build from them a rigorous theory of optics, formalizing how light moves and how vision actually works. The architecture of seeing was always there, etched into the behaviour of light itself.

Understanding the neural implementation only happened relatively recently. Less than 100 years ago, in the 1950s and 60s, neurophysiologists David Hubel and Torsten Wiesel placed electrodes in cat visual cortex and discovered that individual neurons weren’t responding to the entire image, but to specific features. Some neurons fired only when shown vertical edges, and others for horizontal lines. Still others responded to particular angles, specific orientations, and defined directions of movement.

They made an early approximation that the visual system operated hierarchically. In this hierarchy, early neurons detected simple features like edges, contrasts, basic shapes. These then fed into neurons detecting increasingly complex combinations like corners, curves, textures. Eventually, higher regions integrated these into object recognition for things like faces, bodies, predators, and prey. The brain seemed to build understanding layer by layer, abstraction by abstraction.

In the 1980s, Kunihiko Fukushima’s Neocognitron proposed layered, shift-tolerant recognition that directly mirrored the idea of simple features composing into complex ones. Then in 1998, Yann LeCun’s convolutional neural networks (CNN) retained the core architectural ideas, but made them practical and scalable.

The convolutional approach worked because it borrowed biology’s core insight. Each layer detects features like edges, textures, and patterns in ways aligned with early understanding of visual processing. Pooling operations provide spatial invariance, which allows recognition regardless of the exact position, and deeper layers combine simple features into complex representations.

Our visual systems have already solved the problem of compressing high-dimensional input into usable structure. Computer vision was just learning to do this. The cat’s visual cortex was reverse engineered into silicon, opening up a world of possibilities.

Computers Learn to See Cats

But having an architecture that can theoretically see doesn’t mean it can actually see. You could build a convolutional network that mimicked visual hierarchy, but making it work requires something our own biological systems do from infancy: taking in massive amounts of training data through exposure to the visual world around us. We train our vision through direct experience, and computer vision needed an artificial equivalent.

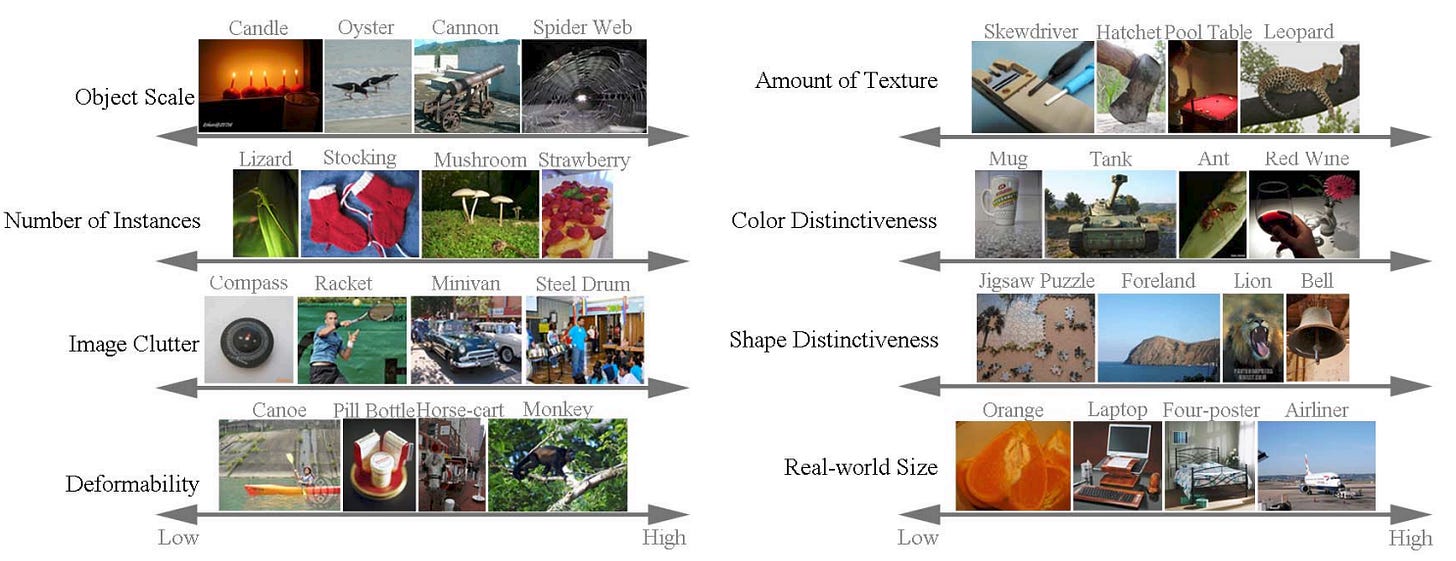

Fast forward to 2010, the ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge (ILSVRC), a competition to classify millions of everyday photos into 1000 categories was launched. Fei-Fei Li, was the central driver behind ImageNet (inspired by WordNet) and helped catalyze ILSVRC as a standardized benchmark. At the time, much of computer vision was betting on the need for better algorithms, whereas Li’s bet was that the limiting factor was data scale and label quality.

The goal of the competition was computer vision capable of broad object recognition with human-like accuracy across messy real world variation. Distinguishing cats from dogs was the easy part, but seeing subtler differences, like the patterns of a leopard versus a jaguar, required something more sophisticated.

The ImageNet dataset of photos itself was interestingly built through paid crowdsourcing on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk platform. The images were collected from the web and then manually labeled by this global workforce of human annotators.

But training deep networks on millions of images demanded computational power that traditional CPUs couldn’t efficiently provide. The solution came from an unexpected direction: gaming. NVIDIA enters the chat.

NVIDIA had released CUDA in 2007, a programming framework that made their graphics cards programmable for general computation beyond rendering video games. The GPUs inside gaming rigs were, at their core, massively parallel matrix multipliers consisting of thousands of small cores executing simple operations simultaneously. That just happens to be exactly what neural network training requires.

NVIDIA CEO Jensen Huang described the first external non-gaming use case for GPU parallel processing being researchers at Mass General that were using the GPUs for CT reconstruction. This was inspiration that led Huang and his team to enable repurposing across multidisciplinary domains.

Exaptation as corporate philosophy. Gaming architecture just waiting to take flight somewhere else.

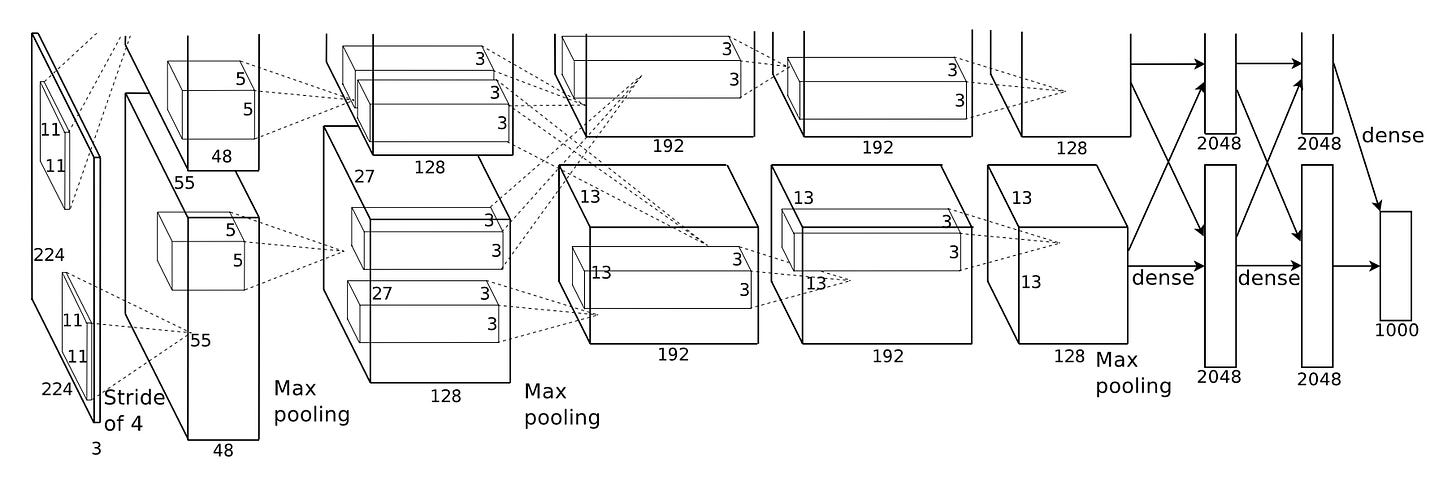

In 2012, that philosophy collided with Li’s data bet. Alex Krizhevsky, Ilya Sutskever, and Geoffrey Hinton entered the ILSVRC and they won by a landslide with their deep CNN called AlexNet (open source code here).

AlexNet was trained in about 5 to 6 days on gaming GPUs, specifically two NVIDIA GTX 580 graphics cards designed to render video games, repurposed to multiply the matrices that neural networks require.

The architecture consisted of five convolutional layers followed by three fully-connected layers, using convolution operations to slide filters across images and detect features at increasing levels of abstraction.

AlexNet became the blueprint for a new generation of visual models. The core principle was learning that familiar “hierarchy of features”: the first layers learn simple edges and colours, middle layers learn textures and patterns, and the final layers learn to recognize complex objects.

AlexNet proved that by training a network with many layers on a massive dataset, you could teach a machine to “see” with high accuracy, at large scale.

A silicon implementation of what Hubel and Wiesel had found in cat brains, running on hardware built for gaming, could now classify images of cats.

Classifying Cats to Cancers

This led to the realization that the features these object recognition models learned to recognize were not specific to images of a particular domain. Edges, textures, shapes, and colors are universal visual markers. A network trained to discern the subtle fur patterns of a leopard could, in theory, be retrained to spot the signs of a malignant mole.

This insight gave rise to the practice of transfer learning, which became the standard for biological image analysis. Instead of building a whole new network from scratch (à la Nara Smith), a process requiring tons of new data and computational power, researchers could take a powerful model, which was already pre-trained on a large data set (like ImageNet), and simply fine-tune it on a smaller, specialized medical dataset.

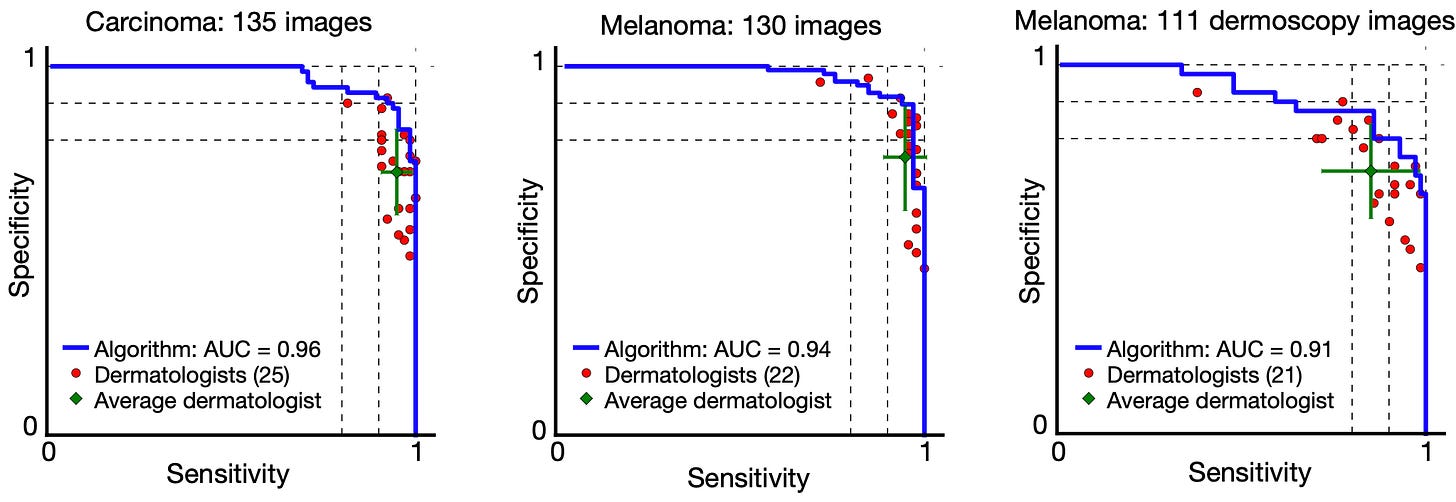

A 2017 Nature paper by Esteva et al. provides a great example of this. The team used a GoogleNet Inception v3 CNN (direct descendent of AlexNet), pre-trained on 1.28 million ImageNet photos, and retrained it on a dataset of 129,450 clinical images of skin lesions (important to note that having that many clinical images is still quite a substantial data set). They didn’t need to invent a new architecture, they just needed to repurpose (exapt) a powerful, existing tool built for an entirely different purpose.

Their CNN was tested against 21 board-certified dermatologists on two critical tasks: identifying common keratinocyte carcinomas and identifying deadly malignant melanomas. As shown in the paper’s receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, which plot the trade-off between sensitivity (finding all cancers) and specificity (not misidentifying benign lesions), the CNN’s blue performance curve envelops the individual performance points of nearly all the human experts. The algorithm achieved performance on par with dermatologists.

The exaptation proof was in the pudding. A tool designed for web search and photo organization was repurposed into a medical grade diagnostic instrument.

But Where is The Cat?

Now, while AlexNet could tell you if an image contained a cat, it couldn’t tell you where in the image the cat was. For tasks like autonomous driving or robotics, knowing the precise location of every object is critical. This is the challenge of semantic segmentation, assigning a class label to every single pixel in an image.

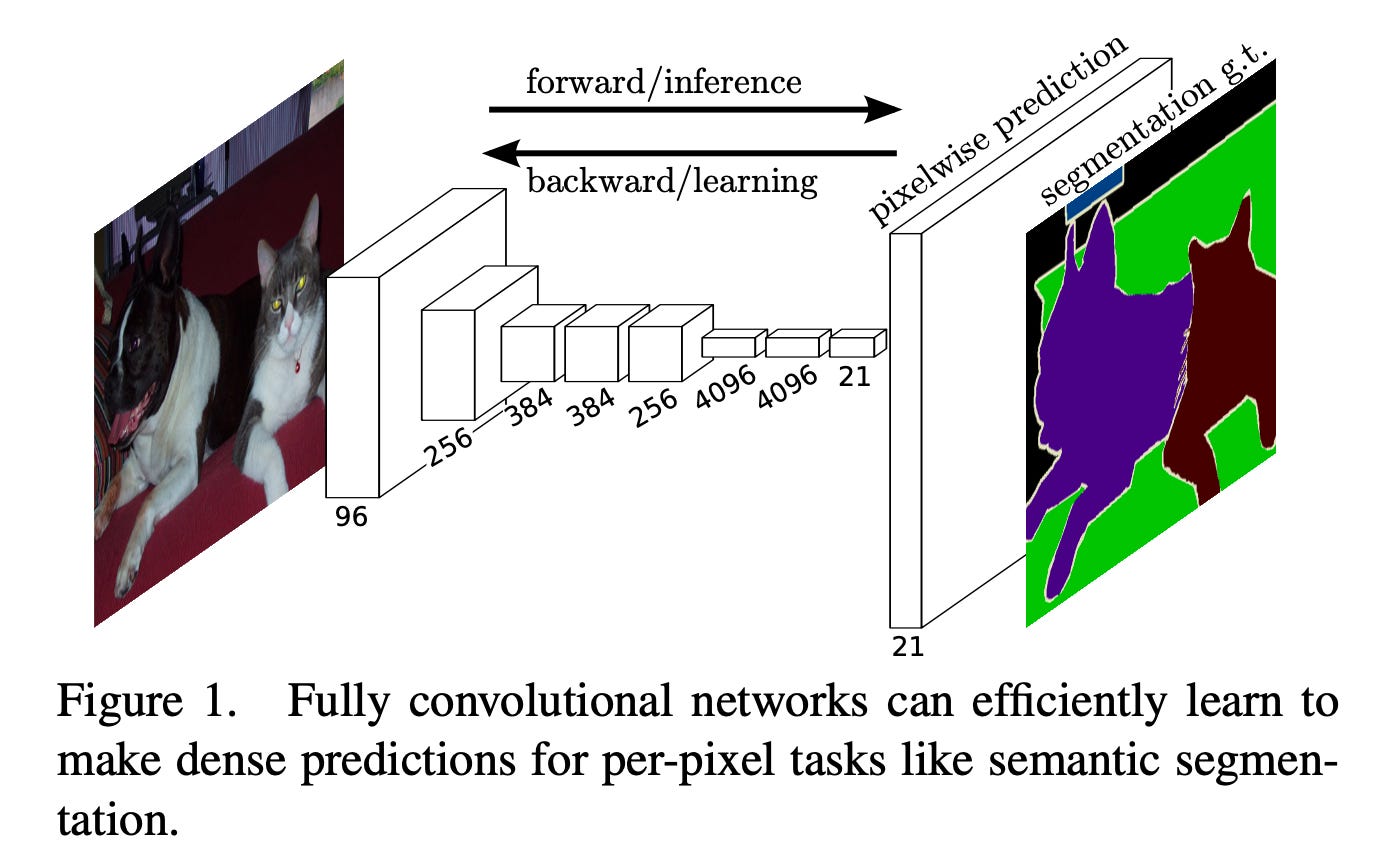

The foundational paper by Long, Shelhamer, and Darrell in 2015 (preprint 2014), “Fully Convolutional Networks for Semantic Segmentation,” introduced a transformative architecture.

In traditional CNN classifiers, the network eventually collapses the feature maps into a single vector, so it can output one category for the entire image. The key insight of a Fully Convolutional Network (FCN) is basically: don’t force everything into one vector at the end and keep it spatial. What comes out isn’t a classification but a map where every pixel gets its own label.

When this was trained on things like large street scene datasets, FCNs learned to label pixels as roads, pedestrians, cars, or buildings, which is exactly the kind of perception pipeline early autonomous driving systems needed.

FCNs Exapted to U-Net

Now what was even more interesting here is that the computational challenge of outlining a road in a street photo is fundamentally identical to outlining a tumour in an MRI scan or tracing the membrane of a single neuron in a microscopy stack. FCNs provided a framework for moving beyond classifying an entire image to understanding the precise location of every component within it.

However, biomedical imaging presented unique constraints that the streets did not. Medical datasets are noisy, boundaries can be faint, they’re expensive to acquire and challenging to annotate. Every cell boundary, every membrane, every nucleus is traced by expert hands. While ImageNet contained millions of labeled images, biomedical researchers might have tens of images.

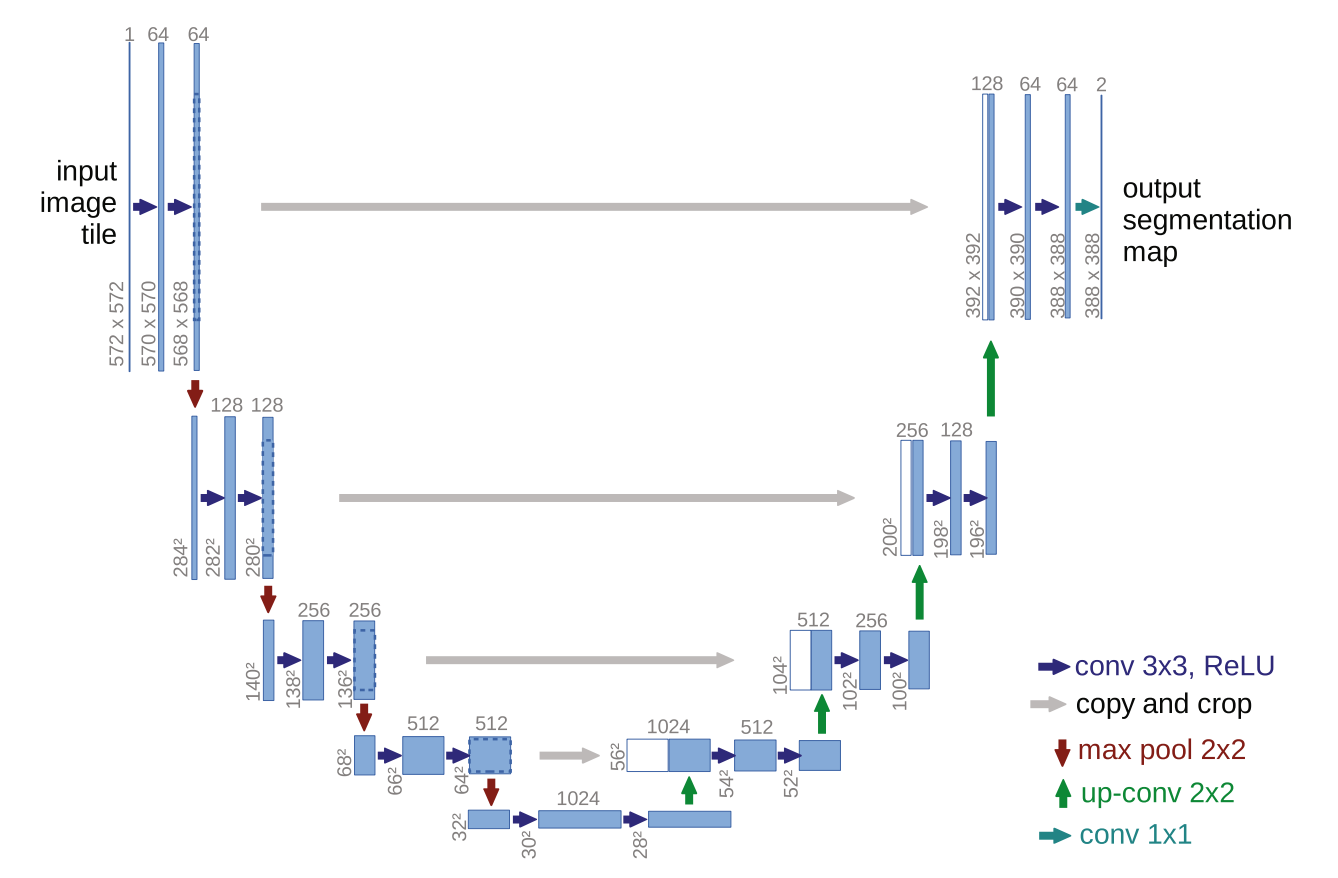

This led to another co-evolutionary step. In 2015, Ronneberger, Fischer, and Brox at the University of Freiburg confronted this specific challenge by training neural networks to outline individual cells in noisy microscope images with only 30 annotated training examples. Their solution was U-Net, which represented an exciting evolution of the FCN architecture, specifically designed for biomedical constraints.

The U-Net architecture embodies elegant symmetry in its literal ‘U’ shape, directly visible in their original paper’s Figure 1 below.

U-Net builds directly on the FCN shift of keeping predictions spatial instead of collapsing everything into one label. But FCNs typically downsample and shrink the feature maps as they go deeper, and when you later upsample to get back to the original size, some fine-grained detail is already gone, so boundaries can come out blurry.

The U-net instead has a contracting path on the left side of the ‘U’ above that repeatedly downsamples, compressing the image into abstract features that capture the ‘what’. On the right side it has an expanding path that upsamples to reconstruct the ‘where’. The key upgrade here is skip connections, which copy high-resolution features from the contracting path directly into the matching stage of the expanding path, restoring the lost detail and producing much cleaner edges.

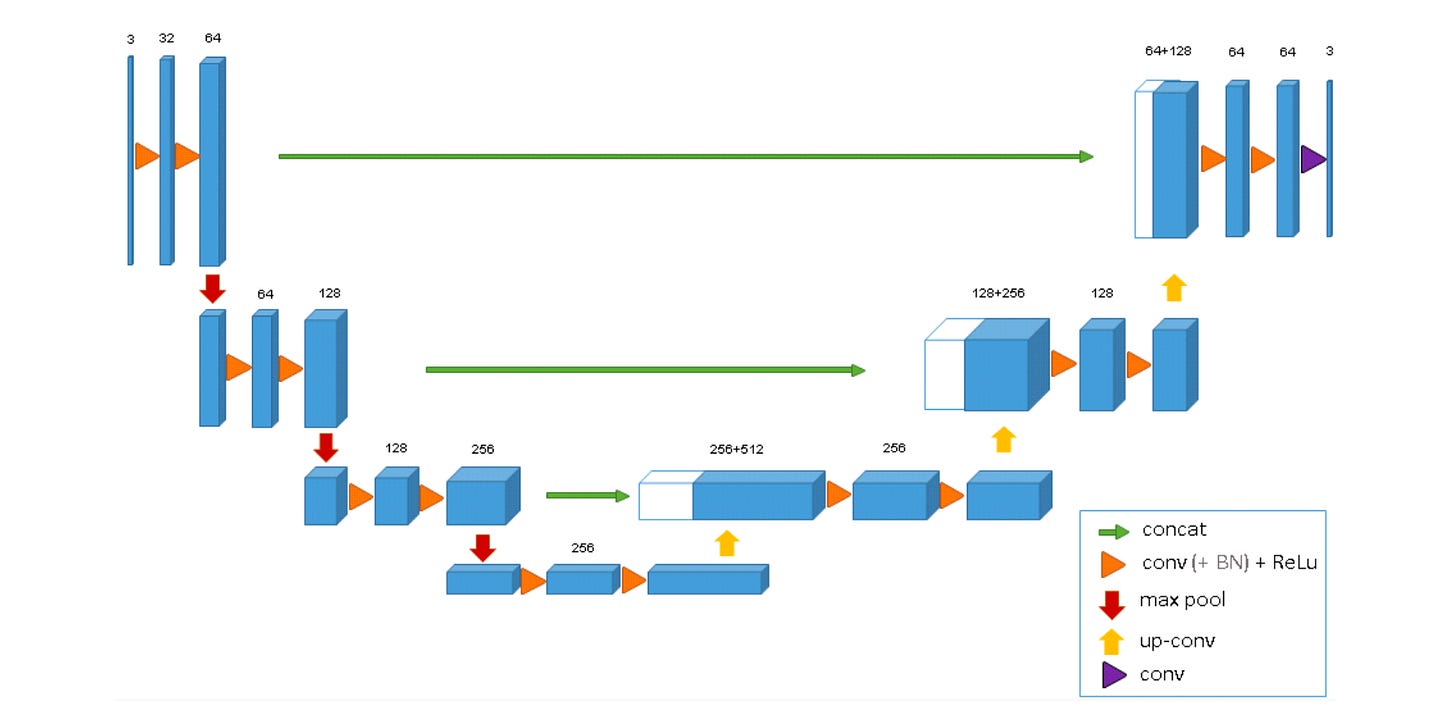

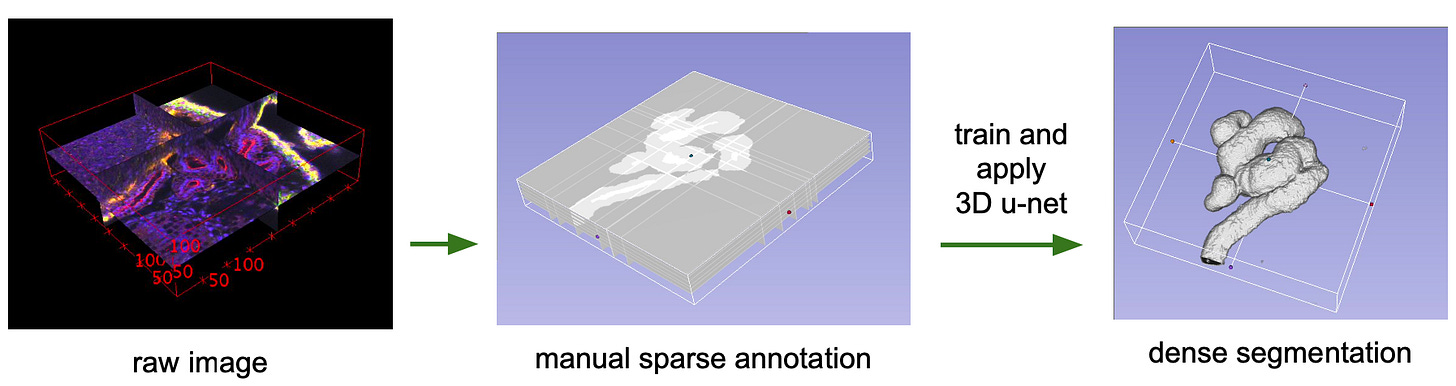

This was then quickly adapted into the 3D U-Net by Çiçek et al. in 2016 for volumetric medical data.

They extended the U-Net architecture to solve the problem of segmenting 3D structures, like those in a CT scan of a Xenopus kidney.

The 3D U-Net keeps the same ‘U’ shaped encoder decoder with skip connections, but takes the whole pipeline into volume: every convolution, pooling step, and upsampling operation now runs in 3D, so the contracting path learns full volumetric context and the expanding path rebuilds volumetric detail, with skip connections preserving structure across scales.

So now instead of needing an expert to label an entire 3D scan, a human can annotate a handful of representative 2D slices, and the model learns to infer and segment the rest of the volume, translating it into a dense 3D map.

The same underlying logic reappearing wherever the problem demands it. Keep the ‘what’ and the ‘where’ aligned across space, whether navigating city streets or mapping 3D organs, across pixels, cells, or voxels.

3D U-NET to AI Art

I fear the biomedical segmentation feat of the 3D U-NET might also, remarkably so (!), be responsible for your AI art (or slop depending on how you look at it).

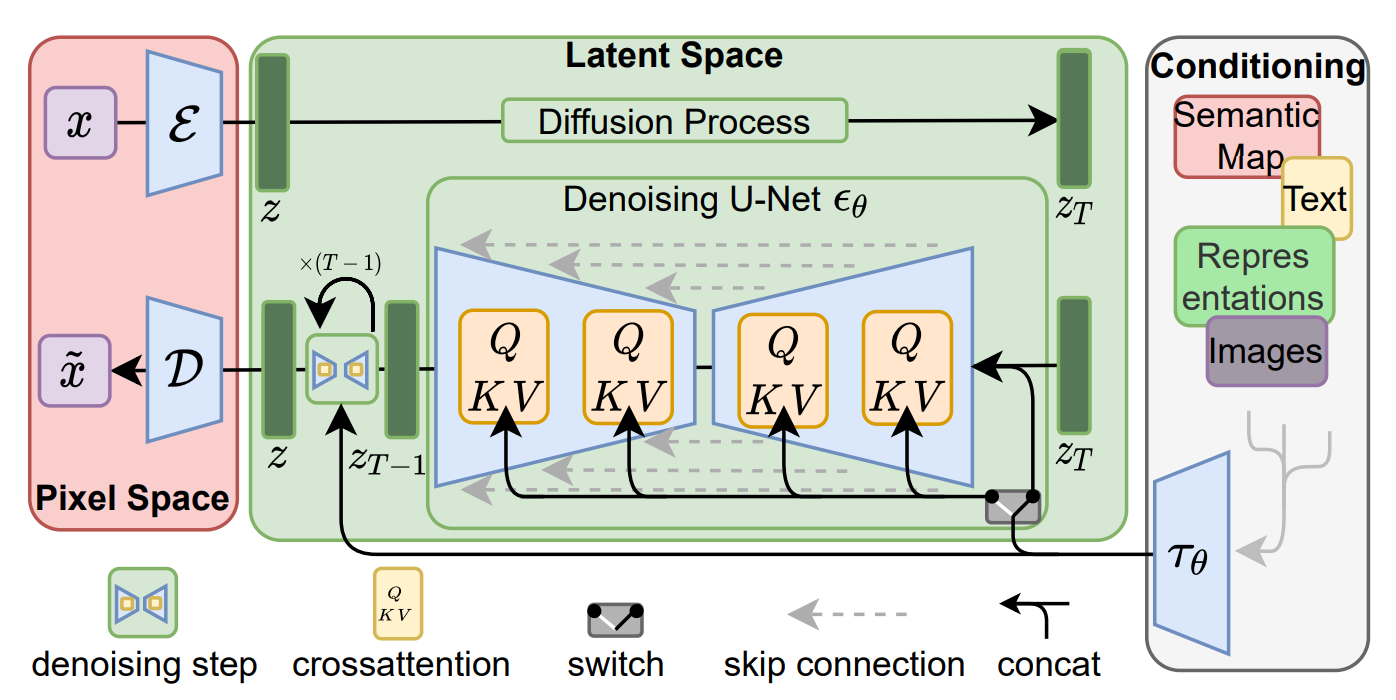

For years, U-Net remained tethered to the world of medical imaging, peripheral to the broader AI zeitgeist. Then, around 2021, diffusion models emerged, a fundamentally different approach to image generation.

Diffusion models approach image generation through controlled destruction and reconstruction. During training, you take a real image and gradually corrupt it with noise until it’s essentially static. The network is learning the reverse move of how to predict and remove noise step by step. The model then generates an image in reverse. It starts from almost pure static/noise, then applies the same neural network over and over to remove a small amount of noise at each step, until structure appears and you get closer and closer to an image.

The network needs to keep the rough layout and shapes, as well as the more local edges, textures, and small details consistent at once. This is what the U-Net architecture is good at. It can first compress the image representation to capture context, then expands it back to recover detail, and use skip connections to carry high-resolution information forward so it doesn’t lose the sharper details. That’s why U-Net style denoisers sit at the core of diffusion systems like Latent Diffusion and Stable Diffusion.

The architecture that once mapped kidney structures in three dimensions, and traced neuronal boundaries in microscopy stacks…is the same structure that now sits at the core of seemingly magical modern text to image generators like Midjourney and DALL-E.

We’ve gone from biomedical image segmentation to AI generated art.

Exaptation as Conscious Innovation Strategy

We’ve traced a specific evolutionary lineage here. Going from neurons in cat visual cortex extracting features hierarchically to convolutional networks built to mimic that architecture for object recognition. Breakthroughs like AlexNet forming precursors to networks repurposed to diagnose skin cancer. Fully convolutional networks that can learn to segment city streets for autonomous driving birthing U-Nets that adapt those same principles to outline cells with minimal training data. 3D U-Net extending this into volumetric medical imaging. Finally, that same architecture becoming the denoising engine at the heart of AI image generation.

At each step, structures built for one problem got borrowed into new contexts, solving problems seemingly far away from their original designs. This is exaptation. The evolutionary process where a feature developed for one function gets repurposed for something entirely different.

A borderless innovation strategy that evolves freely across fields. Learning to see familiar patterns in unfamiliar places. NVIDIA saw this early and built for it, intentionally creating space and infrastructure that enabled repurposing across applications they couldn’t anticipate.

Let’s imagine all technology as one force, exapting itself into every niche, growing, wet and dry, endlessly exchanging solutions.

Everything is already everything else.