Vibe Coding Biology: The Collapsing Cost of Curiosity

From DNA synthesis ceilings to new assembly architectures, and the converging stack that promises to make rapid biological iteration reality

It’s easy to take for granted knowledge that almost feels intrinsic after spending so much time inhabiting, researching, and dreaming in a particular field. There is a peculiar phenomenology to building expertise where things you once deemed extraordinary slip into the accustomed realm of the ordinary.

I was reminded of this recently when expressing the challenge of DNA synthesis screening for biosecurity to someone when they stopped me mid-explanation and looked at me as if I said we were manufacturing moonlight.

“Wait… what do you mean ‘synthesizing DNA’? We can make DNA?!”

Not only can we make DNA, we have been making it since the 1950s. Synthetic DNA is perhaps the only true artificial intelligence.

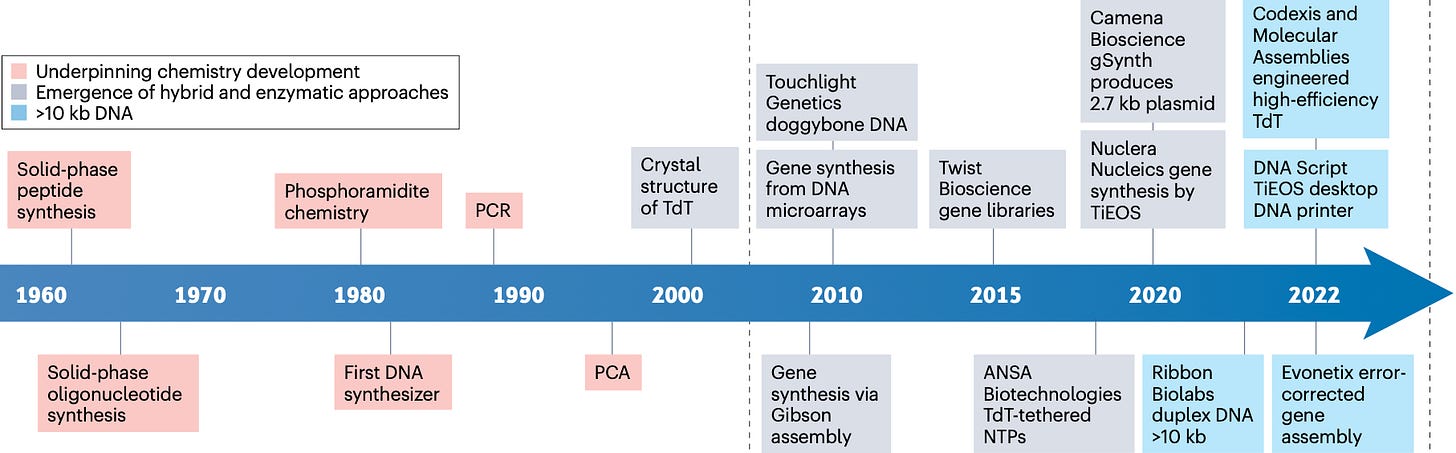

In fact, though it might seem counterintuitive, the ability to chemically synthesize short fragments of DNA came even before our ability to reliably sequence DNA.

The first fully functional synthetic gene was synthesized by Nobel Prize Winner Har Gobind Khorana in 1970. We have been making functional synthetic DNA even before having an alternative to pipetting with one’s mouths.

Since then, 50 years of incredible growth as co-constructors of life have passed. However, the trajectory of this DNA techno evolution has been characterized by an interesting oscillation in our technological capabilities.

On one hand, DNA sequencing costs have plummeted faster than Moore’s Law, and the tools for editing existing genomes with CRISPR-Cas9 and its derivatives are becoming ubiquitous. Even the AI generated genomic revolution is underway. Yet, the capacity to do efficient, high accuracy, large scale DNA assembly has remained a persistent and frustrating bottleneck.

But it appears that things are about to change. Sidewinder, a new DNA assembly architecture has been invented with the potential to unlock critical capacity, and reinvigorate the synthetic biology promise land. From medicine, to materials, DNA data storage, genome scale synthesis, and beyond.

We are witness to an interesting moment in time where key technologies are converging and unveiling what I can only call the biological vibe coding era. An era where we finally have the tools to appreciate and explore, rather than attempt to reduce the inherent sophistication of biological systems. One where the limitations shift from the prevailing physical constraints to our imaginations.

Limits of DNA Synthesis

Since the advent of recombinant DNA technology, virtually all DNA assembly methods have relied on the joining of overlapping “sticky” DNA fragments. But why do we even need to assemble DNA? If we can synthesize DNA, why not just print designs in their final forms? Especially considering that the synthesizing cost per base pair (bp) of DNA has become remarkably cheap.

Major industrial DNA synthesis company Twist Bioscience can now produce DNA for around $0.07 per bp thanks to their super high throughput silicon microarrays. Companies like Ansa Biotechnologies use newer enzymatic methods that don’t rely on traditional phosphoramidite chemistry, avoiding the production of toxic chemical waste. The company DNA Script has even made benchtop synthesizers, moving DNA production in house.

DNA synthesis is getting cheaper, greener and more portable.

But there’s a pretty hard ceiling when it comes to achieving longer single synthesis length. With traditional phosphoramidite synthesis, the yield of pure DNA drops exponentially with each added base, collapsing to just 13% for a 200 bp strand.

We’re seeing some cracks in the 200 bp chemical synthesis ceiling from a recent approach by Yin et al. (2025) that suggests the ceiling wasn’t the chemistry, but the physical environment. By switching from porous beads to a smooth surface support, the researchers eliminated the physical crowding that typically kills yield, successfully printing a single 1728 bp gene directly at never before seen accuracy levels. This is still at low throughput academic scale, but it will be interesting to see its industrial potential.

Newer enzymatic and hybrid approaches are pushing past chemical limitations by using enzymes like Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl Transferase, a DNA polymerase isolated from calf thymus that was discovered in the 1960s. These methods are capable of generating longer fragments at the kilobase length. Ansa even recently introduced up to 50kb clonal synthesis starting at 28 cents per base pair with turnaround times less than 25 business days.

Progress is real, but the scale, and complexity that can be synthesized remains humbling. Even with clonal 50 kb synthesis capability, compared to whole-genome projects in the millions or billions of base pairs, with high complexity, repetitive regions, significant and tedious assembly is unavoidable.

The DNA Assembly Bottleneck is Breaking

The assembly step is where things tend to fall apart. It’s where wet lab scientists must reach Gandalf levels of cloning wizardry to actualize their designs.

Since being introduced in 2009, Gibson Assembly remains the workhorse for everyday cloning. The mechanism requires an enzyme to eat away at the ends of DNA fragments to expose single stranded overhangs. When these typically 20-40 base pairs overlaps are complementary, they stick together. A polymerase fills gaps, and the ligase seals everything into your final construct.

This can be great for putting together a handful of fragments, but beyond that, efficiency collapses. More critically, Gibson Assembly is acutely sensitive to sequence composition. When you have DNA rich in guanine and cytosine (high GC content), your DNA can form stable hairpin structures that prevent fragments from connecting. Repetitive sequences confuse the system entirely, so if your overlaps look identical, the assembly machinery can’t tell different intended points of connection apart.

Golden Gate Assembly is another commonly used assembly method. It uses specialized enzymes that cut DNA at a precise distance from the recognition sites, creating unique four nucleotide overhangs that act as site specific connectors. This enables directional assembly of multiple fragments with high accuracy.

The key here is the need to remove any internal recognition sites through sequence modifications. This works fine for standardized part libraries but becomes impractical when working with natural genetic sequences where you don’t want to or can’t freely change the sequence. This method requires you to modify the biology to fit the assembly method.

Zoom out further and you find even earlier but still widely practiced polymerase driven strategies. There’s Polymerase Cycling Assembly (PCA), and Circular Polymerase Extension Cloning (CPEC), where DNA fragments act like primers for one another and a polymerase extends across overlaps through thermal cycling. These approaches can be surprisingly effective for clean templates, but they still inherit the same molecular liabilities of secondary structure, repeats, GC-bias, error propagation.

Then, when you push into the big leagues in terms of scale, with hundreds of kilobases to megabases, you often stop pretending this is an in vitro problem at all and hand it back to biology. This is where you turn to Saccharomyces cerevisiae (yeast). Yeast cells have remarkable homologous recombination machinery that can assemble huge DNA molecules that would physically break under normal lab handling.

Transformation Associated Recombination (TAR) cloning has successfully assembled the iconic 1.08 megabase Mycoplasma mycoides genome and synthetic chromosomes exceeding a million base pairs. While yeast acts as this necessary living chaperone to prevent molecular shearing at the megabase level, the process remains slow and prone to unintended deletions and rearrangements, particularly in GC rich or highly repetitive regions where native recombination logic fails.

These conventional methods also often rely on the DNA sequence itself as the assembly instructions. The overlapping regions guiding fragments together become part of your final genetic code.

For example, in Gibson Assembly, those overlaps must be thermodynamically balanced and stable enough to connect, but not so stable they form unwanted structures. With repetitive sequences, overlaps become identical and the system can’t distinguish between thm. In a complex assembly with varying sequence composition, you need overlaps with wildly different properties, but you’re constrained to running everything at compatible temperatures.

The bottleneck isn't just fragment count or reaction efficiency. It's architectural. You can't cleanly optimize the assembly instructions without touching the biology you're trying to preserve, as they are deeply entangled.

A New Architecture: Sidewinder

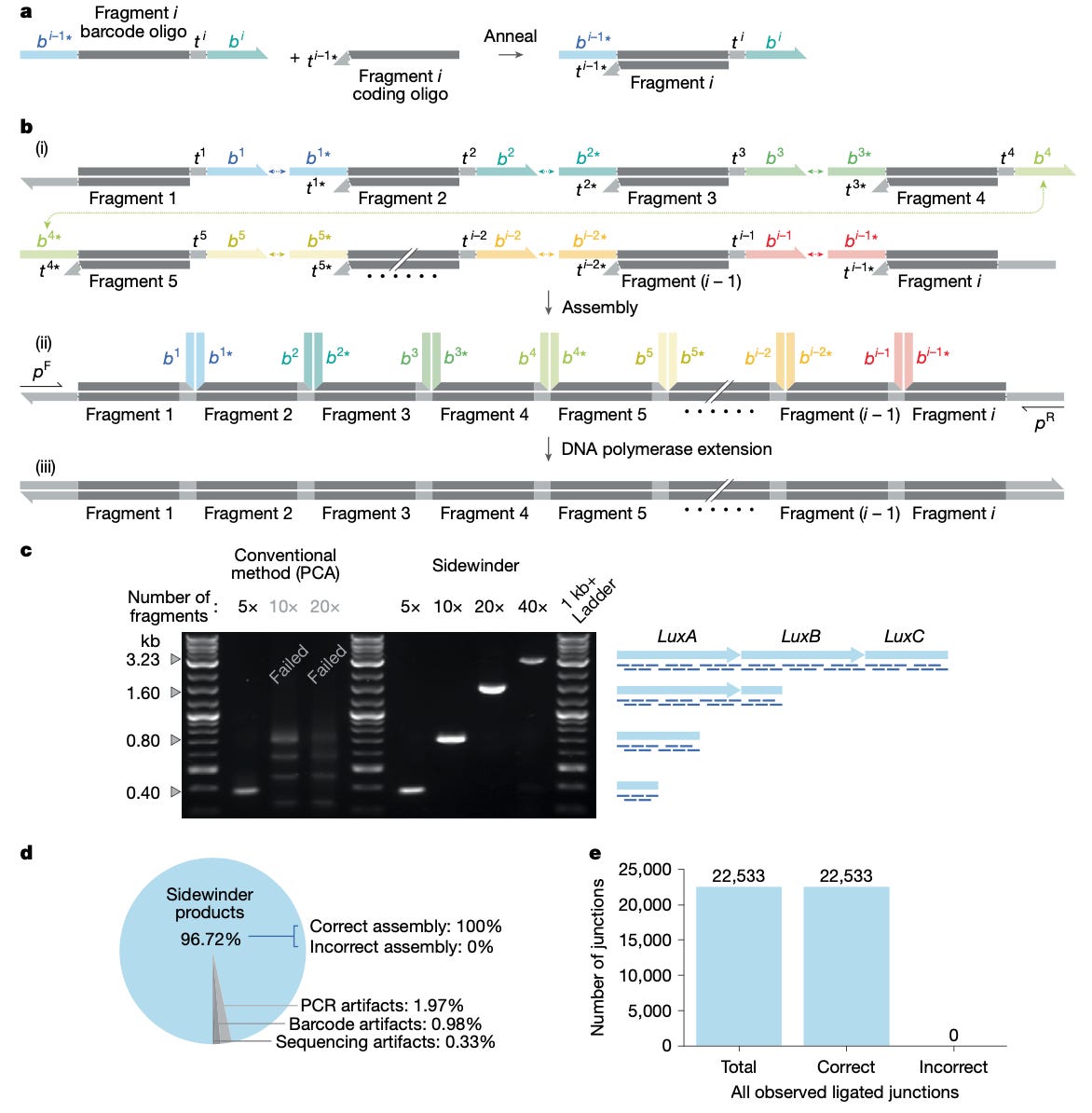

On January 2026, the Robinson et al. (2026) Nature paper introduced a new DNA assembly architecture called Sidewinder.

Instead of fragments meeting end to end, Sidewinder uses what is referred to as 3 way junctions. In addition to the two fragments you’re bringing together, there is a third strand, the Sidewinder helix, which is pure scaffolding that gets removed after assembly.

The way that it works is that each DNA fragment in a Sidewinder assembly is processed into a specialized heteroduplex (the two DNA strands are not perfectly complementary to each other) containing two distinct functional regions. The first are toeholds, which are short overhangs that are part of your final sequence but thermodynamically weak, so they cannot connect stably on their own at the reaction temperature.

The second component are barcodes, which are long, unique sequences forming the third helix. The barcodes are completely external to the biological sequence and don’t appear at all in your final construct. This means they can be computationally optimized for perfect orthogonality (non interfering parts) and ideal thermodynamic properties (in terms of melting points) regardless of what you’re actually building.

The reaction runs at a temperature where toeholds can’t anneal alone, but the longer, optimized barcodes remain stable. Unlike more traditional methods, here the fragments cannot interact based solely on their biological sequence overlaps. The barcode sequences hybridize first, bringing the right fragments closer together. This local concentration effect then stabilizes the toehold annealing, forming the 3 way junction. It’s cooperative binding where the junction only forms if both barcode and toehold match.

Ligation gets gated by what is essentially a two factor authentication. It’s an incredibly precise process where experimental data shows that if either the barcode or toehold mismatches, ligation is effectively blocked. After ligation, a DNA polymerase extension step displaces or destroys the barcode oligos, leaving a seamless, scarless double stranded DNA output.

In the authors’ stress tests, conventional oligo based assembly methods (PCA in this case) hit a practical wall somewhere between five and ten fragments, while Sidewinder holds together all the way to a 40 fragment, single pot build, with 100% correct fragment order. Across the 22,533 junctions examined, they also reported zero mis-ligations.

When it comes to GC rich sequence assembly, it successfully assembled the human APOE gene that has segments with up to 95% GC content, as well as the highly repetitive silk protein h-fibroin using identical toeholds, that is identical biological overlaps for all fragments. It is also because the specificity itself is outsourced to the orthogonal barcodes rather than the target sequence that massive scalability is possible, which was demonstrated by the construction of an eGFP library with 17 diversified positions and approximately 92% coverage of over 440,000 variants.

That said, the paper is also clear about what this doesn’t magically abolish. As assembly errors drops, the bottleneck shifts upstream to input oligo quality and complex digital biological design capacity, especially since we now have a third element at the junction point to design.

With Sidewinder, multi-fragment, complex assembly feels less like the hard ceiling and more like a reliable intermediate, which is exactly the kind of shift you need if AI is going to generate many competing designs that we can actually afford to build, test, and iterate in the physical world.

The Convergence: Design, Build, Test, Train

Sidewinder is arriving at a very critical moment where biological design advances are demanding better assembly scale, accuracy and complexity.

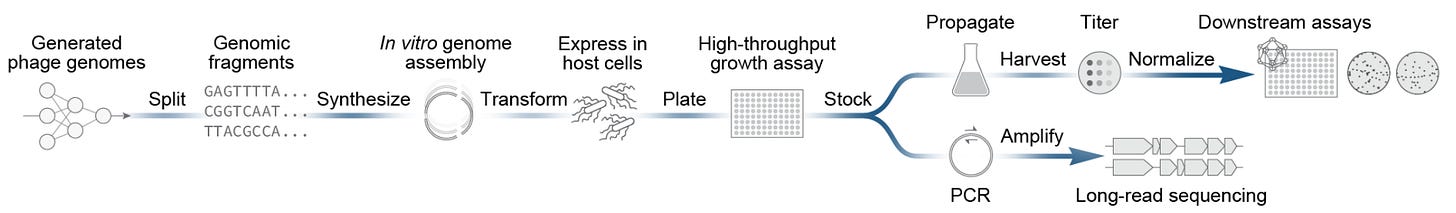

We have genome language models like Evo 2 developed at the Arc Institute, which are trained at single nucleotide resolution across every kingdom of life, learning the statistical and long range constraints that allow whole genomes to form. They don’t just predict potential new sequences, they are attempting to decipher how complete genomic systems are actually held together.

Researchers recently used Evo to generate hundreds of bacteriophage genomes based on the virus ΦX174, a 5.4 kb template with densely overlapping genes where there’s virtually no room for error. They moved 302 AI designs into the physical world, successfully synthesizing 285. After rebooting in E. coli, 16 viable phages emerged, with several even outcompeting the naturally existing ΦX174 in fitness assays.

But even with the relatively manageable genome size of 5.4 kb, 17 of the designs failed at synthesis due to sequence complexity. Generative design capacity has been scaling faster than our ability to build, especially as AI pushes into sequences that are GC rich or highly repetitive, exactly the kinds of structurally inconvenient DNA we’ve historically avoided. Sidewinder has the potential to change that.

Design expands what can be imagined. Assembly expands what can actually be built. Testing closes the loop. The cost of curiosity is rapidly collapsing.

Once you have the power to generate and construct thousands of variants, the question then shifts to how do you test them?

A critical third wave is quietly building this future. High throughput biological testing infrastructure is maturing through automated foundries, microfluidic culture systems, and increasingly sophisticated phenotyping assays. A truly viable feedback loop is forming where AI/ML is harnessed to generate designs, digital biology gets assembled reliably, automated systems test thousands of variants, and the resulting data feeds back to refine the models. Each cycle compounds and we enter new biotech spring, where the cost of building and testing a design approaches the cost of simulating it.

This convergence of course carries risks that scale with capability. This isn’t a reason to stop. It’s a reason to proceed with both urgency and deliberation.

Genyro

The convergence is already spinning out of the lab. Genyro has exclusively licensed Sidewinder from Caltech and brought together founding expertise spanning both the new assembly tech and the generative AI genomic work at Arc Institute.

The company represents a strategic bet on vertical integration. Not just better synthesis services, but they are doubling down on both ends of building with biology.

Sidewinder’s strategic positioning allows it to take whatever oligo supply chain wins, and make long, complex constructs less sensitive to the payload sequence. In fact, smaller oligos are also ideal as it’s two factor check before ligation would add another layer of proofreading for accuracy to perfect final assemblies.

Twist Bioscience currently dominates high throughput chemical synthesis, producing short oligos at scale cheaply. Sidewinder can use cheap Twist oligos as starting material to build complex, multi-piece constructs, making Twist an ideal partner.

The real competitive pressure might land on automated assembly platforms that rely on conventional methods. Sidewinder represents a fundamentally better approach for higher fidelity, better complexity tolerance, and fewer sequence dependent constraints.

But the deeper question is what market Genyro is actually targeting. Are they selling synthesis services? Building a platform for others? Pursuing internal therapeutic development? Vertical integration suggests ambitions beyond pure service provision. A company that has both deep design and build capabilities could really aim to capture value from applications rather than just enabling them.

Vibe Coding Era of Biology

We’re entering the vibe coding era of biology.

The name might sound whimsical, but it captures something essential about what’s becoming possible. For decades, synthetic biology operated under an engineering paradigm: design parts with predictable functions, assemble them into circuits, debug until they work as specified. It was biology forced into the mold of engineering.

Reducible, modular, controllable.

That approach delivered genuine successes but always struggled against biology’s inherent nature. Living systems are deeply contextual, exquisitely sensitive to conditions we barely understand, and prone to emergent behaviours that defy our simple predictions.

The convergence of tools we’re witnessing doesn’t solve this complexity, it finally gives us the infrastructure to work with it rather than against it.

This is vibe coding. Not because it’s imprecise or unrigorous, but because it embraces working with biological systems as generative partners rather than programmable machines. You design something with intent, but you’re also curious about what it will reveal. You build variants not just to optimize toward a target, but to understand the shape of the possibility space. You test to learn, not just to validate.

You simply can’t force the vibe, you have to feel it.

This was so well explained Ayan!

Thank you so much for putting this article together Ayan! I enjoyed it.